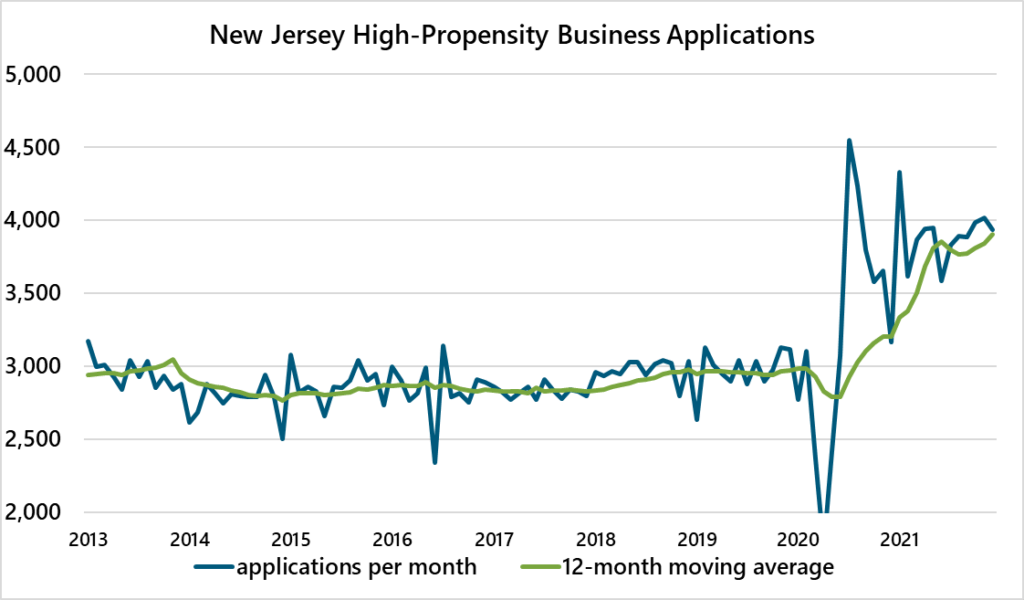

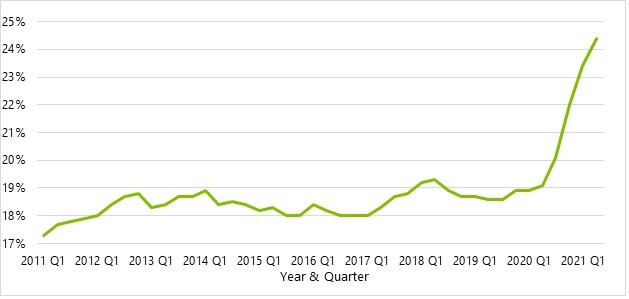

Sometimes, a shock as damaging as a pandemic has a beneficial underside for the economy. For example, we’ve seen a surge in entrepreneurship emerge from the COVID-19 economic shock, as evident in a proliferation of applications to start new businesses. The chart below shows the rate of “high-propensity” business applications filed in New Jersey. As the chart shows, the pace of these applications increased from a rate of approximately 3,000 per month pre-pandemic to near 4,000 now – up more than 30%. The high propensity distinction is important, as these are applications for new businesses likely to be incorporated and create positions for new workers, as separate from applications for businesses likely to be unincorporated sole proprietorships. In this way, these businesses are likely to provide the main sources of income for their owners and provide employment for others.

The cause of this jump in business creation is up for dispute. From our lens, a mix of jobs lost and abundant opportunities to innovate encouraged many people to venture out on their own instead of relying on the status quo. The benefit of this entrepreneurship wave is likely self-evident, but it’s worth noting that entrepreneurship benefits the economy as a whole as well as the individual entrepreneurs. For the economy, entrepreneurship drives the evolution necessary to keep an economy growing. For individuals, entrepreneurship and the value created therein generates economic opportunities and wealth.

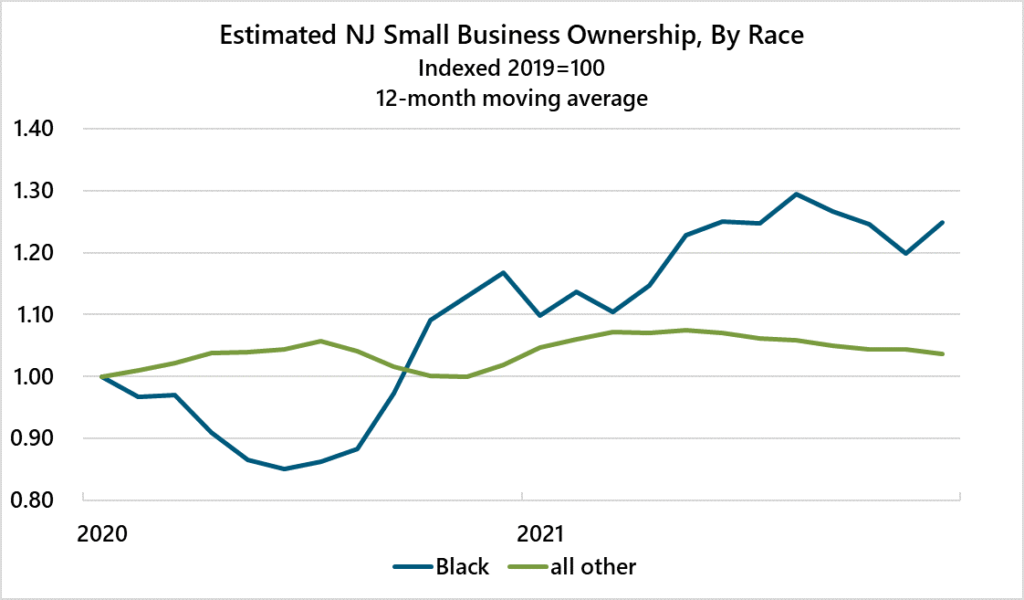

So, who are all these new entrepreneurs? For New Jersey, the evidence suggests a growing share of these entrepreneurs in New Jersey are Black. There are few datasets that provide information on business ownership by race, and the ones that do exist tend to release data with a one-to-two-year lag. Thus, if we want to examine in real time what is happening to business ownership by race, we need to rely on proxies of business ownership.

To this end, we follow a method used by Dr. Robert Fairlie[1] with University of California, Santa Cruz, to estimate small business ownership by race using Current Population Survey (CPS) microdata on self-employment. The CPS is a monthly nationwide survey of individuals that includes questions on labor market status, such as employed or unemployed and, if employed, whether the individual is salaried worker or self-employed. As did Fairlie, we use data on self-employment as a proxy for small business ownership. Fairlie reasoned business ownership could be estimated this way because, if a person is a small business owner, that person is going to identify as self-employed. Moreover, we only include self-employment where it is indicated as the primary employment source. Many people are employed in a wage and salary position and own a business as a secondary source of income, and we do not wish to include these estimates in our dataset.

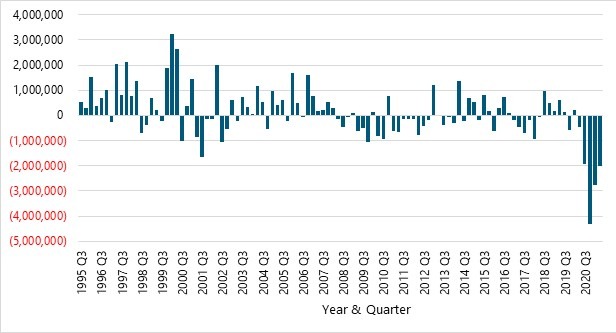

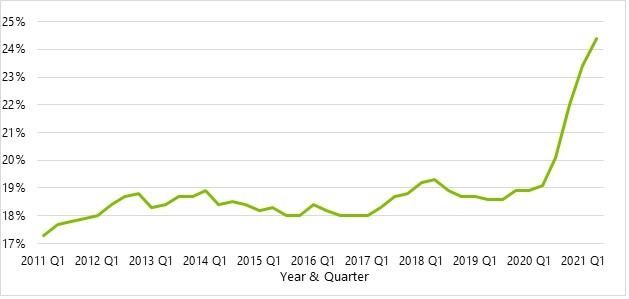

The chart below shows the growth of small business ownership by race, indexed at the 2019 level = 100. We are forced to smooth the data using 12-month moving averages as the data are not seasonally adjusted and are very volatile on a month-to-month basis.

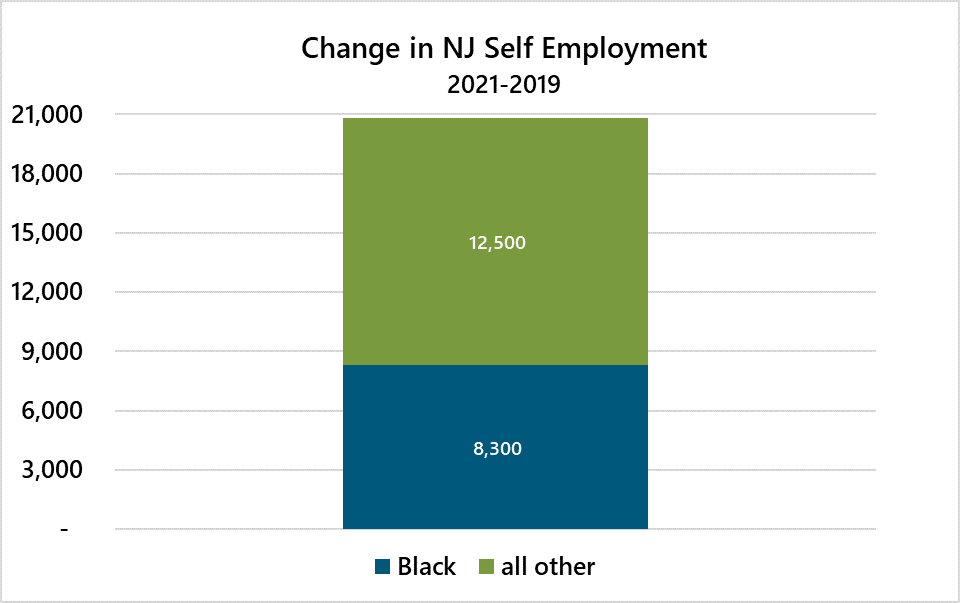

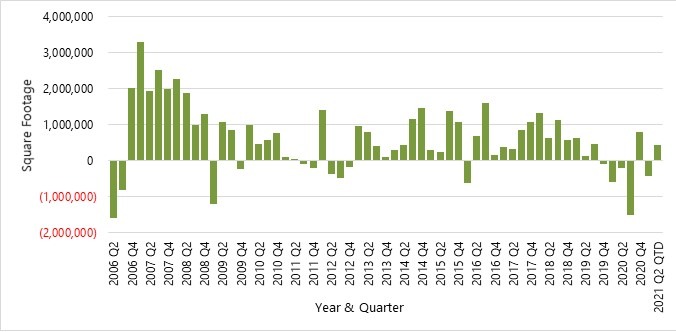

As the above chart shows, Black people were much more likely than the rest of the population to suffer a loss of small business at the start of the pandemic. But since that time, Black business ownership has surged. Relative to the 2019 level, Black business ownership is up approximately 25%. This compares to around 4% for the rest of the population. This comparison between Black and non-Black self-employment is further demonstrated in the chart below, which shows the change in self-employment in 2021 relative to 2019. Of the approximately 20,800 increase in self-employment, almost 40 percent is from Black residents. Given Black residents account for approximately 20 percent of New Jersey’s labor force, the 40 percent share of self-employment shows Black residents are taking up a surprisingly large share of recent new business creation.

The evidence of growing entrepreneurship in the Black community is a welcome sign. But, in order for this growth in entrepreneurship to yield long-term results, these small business owners often require outside sources of financial capital to invest in and grow their ventures. Small businesses are usually strapped for cash – most of the money earned goes into paying for the operating costs of the businesses, leaving little for investment. For instance, the Census Bureau’s Small Business Pulse[2] shows that, for New Jersey, the median business has less than three months of free cash on hand. This clearly isn’t enough to invest in and grow the business.

Unfortunately, access to credit is where the Black community has had one of its biggest challenges with entrepreneurship and business cultivation. The New Jersey Economic Development Authority (NJEDA) has been working with the Federal Reserve to understand gaps in credit access for minority small business owners. Our research shows Black people and other people of color are less likely to have access to credit. These disparities are about more than simply being banked or unbanked – there exists more of a middle ground impacted by the strength of relationships and availability of collateral. As part of this work, we will be meeting with credit organizations, such as community banks and community development financial institutions (CDFIs), to better understand how they approach business with minority small business owners and see where gaps in credit access might be closed.

Moreover, in an effort to close some of these gaps, the NJEDA provides credit and grants to small businesses that might not be able to secure traditional bank financing. Our small business products include improvement grants, lease assistance, direct loans and loan guarantees and participations, as well as direct loans to other credit providers such as CDFIs to help lever credit products. The NJEDA also partners with the African American Chamber of Commerce of New Jersey to offer a Small Business Bonding Readiness Assistance Program to help businesses position themselves to bid on government contracts. The NJEDA wants to ensure that all New Jersey businesses have the resources necessary to expand and that our communities have a healthy climate for growth. As the evidence shows a jump in Black entrepreneurship, our hope is that the work being done with the Federal Reserve and through our programs will support access to credit so these businesses can thrive.

[1] See Fairlie, R. (2020). The impact of COVID‐19 on small business owners: Evidence from the first three months after widespread social‐distancing restrictions. Journal of economics & management strategy, 29(4), 727-740.

[2] See January 9 results for New Jersey at https://portal.census.gov/pulse/data/

.jpg.aspx?width=350&height=294)

.jpg.aspx?width=350&height=276)

.jpg.aspx?width=350&height=182)

.jpg.aspx?width=350&height=171)